To the casual viewer, the books on display in the second-floor gallery of the Grolier Club in Midtown Manhattan look like an impressive collection of rare tomes—not unusual fare for the bibliophilic society. There is a worn Ernest Hemingway, a collection of Sappho poems, and an eerie-looking Sylvia Plath cover. Some bear author names that perhaps sound only vaguely familiar: Harriet Vane, Samuel Pickwick, Orlando.

Visitors roam the gallery, eyeing the delicate volumes enclosed in glass cases. Every few minutes, someone giggles. They get the joke: none of these books is real.

The exhibition, Imaginary Books: Lost, Unfinished, and Fictive Works Found Only in Other Books (until 15 February 2025), is the brainchild of the writer and bibliophile Reid Byers. Along with a team of bookbinders and artists, Byers brought to life more than 100 books that he describes as “some of the greatest non-existent works in all of literature”. These include works lost to history, like Lord Byron’s memoirs, which were famously burned upon his death, and books that exist only in fiction, like The Songs of the Jabberwock from Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy from the eponymous series.

GEORGE GORDON NOEL, LORD BYRON, Byron’s Memoirs. Unpublished manuscript. Burned at John Murray’s shop in London on 17 May 1824.

Byron said that his memoirs presented “the evils, moral and physical, of true dissipation”. The manuscript was burned at his orders by John Murray, his publisher, and John Cam Hobhouse in the fireplace of Murray’s shop at Albemarle Street. Only 23 people were permitted to read it. This biblioclasm has been called “the greatest literary crime in history”. Photo: Reid Byers

The works may only be simulacra, but Byers did not make them up. “There’s no way to fake the imaginary,” Shira Buchsbaum, the exhibitions manager at the Grolier Club, tells The Art Newspaper. “These books exist in some plane of being.”

Byers became interested in the idea of imaginary books about 15 years ago, when he was building a jib door in his home library. The hidden doors, which date back to 18th-century European country houses, were originally designed to blend in with walls so that servants could come and go unobtrusively. In the library room, jib doors were covered with book spines and strips of wood that matched the bookcases. Oftentimes, the family would come up with funny book titles to write on the spines. “When I tried to do that,” Byers says, “I got excited about the idea of using books that were lost or didn’t exist.”

Byers began curating a vast list of imaginary books that spans genres and history. The books fit into three categories: lost (books with no surviving copy), unfinished (almost completed but never published, or thought of but never written) and fictive (existing only inside the realm of a novel).

But it was not satisfying to just have false book spines on his jib door. Byers wanted the physical objects. “That’s the experience that makes the hair stand up on the back of your neck,” he says, so he endeavoured to bring these books into the three-dimensional world.

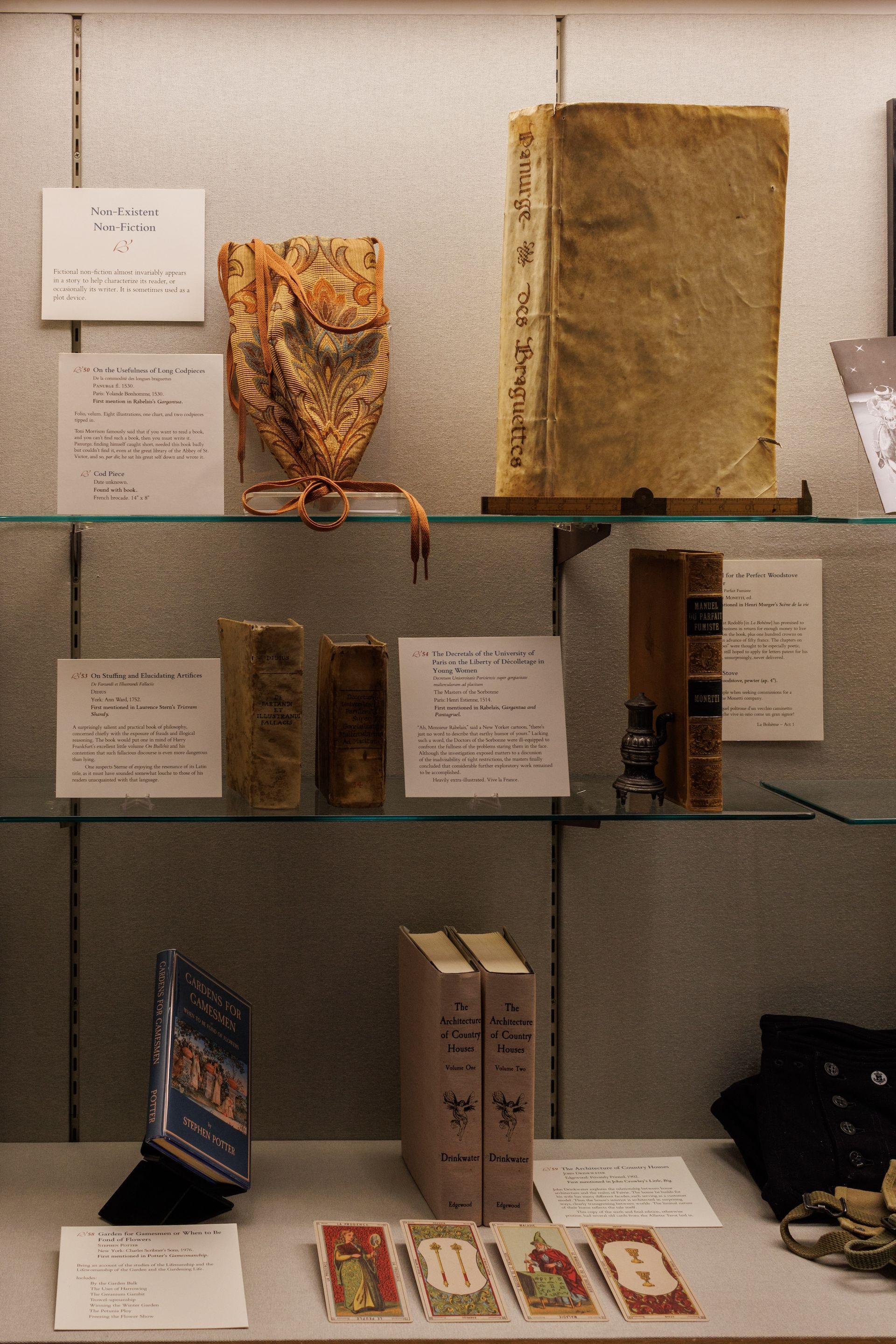

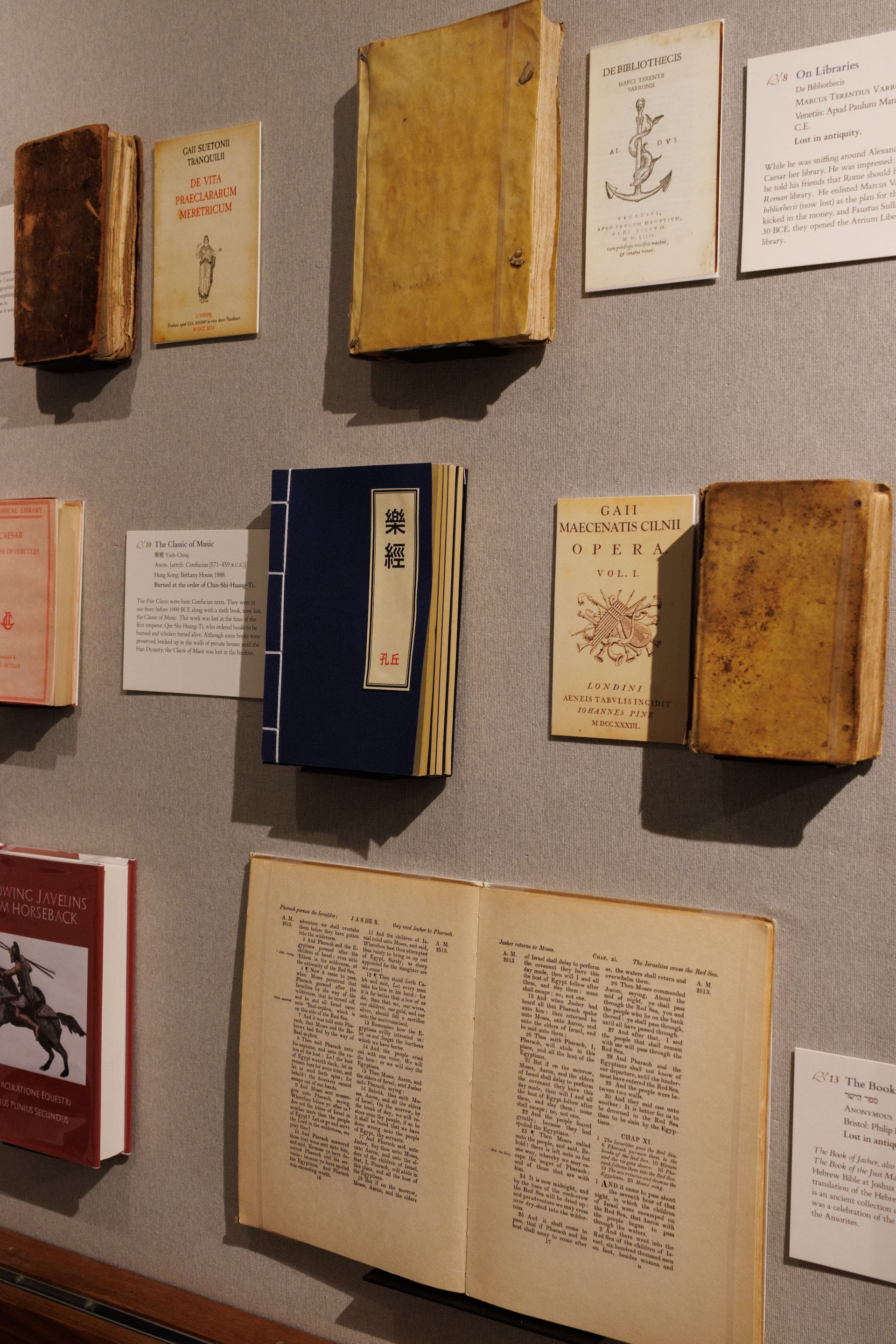

Installation view of Imaginary Books: Lost, Unfinished, and Fictive Works Found Only in Other Books at the Grolier Club, Manhattan Courtesy the Grolier Club

After its stint at the Grolier Club, Byers’s collection will travel to the Book Club of California in San Francisco (17 March-13 July). He also chronicles the project in his very real book, Imaginary Books: Lost, Unfinished, and Fictive Works, out next month

Though Byers does not consider himself an artist, the exhibition is indeed a work of art. Examining his collection, patrons encounter The Octarine Fairy Book, a children’s book that appears in Terry Pratchett’s The Colour of Magic. It is bound in the fictional, magical colour octarine, “said to be visible only to wizards and cats”, reads a placard beside the book.

On another shelf sits a sickly looking copy of Death in the Pot, one of the mystery books penned by Dorothy Sayers’s protagonist Harriet Vane in Strong Poison. The book is wrapped in a green- and red-splotched cloth—supposedly traces of arsenic and cyanide.

Across the room, there is a non-existent work of nonfiction called Thoughts on the Prevention of the Diseases most usual among Seamen, which is referenced in Patrick O’Brian’s Desolation Island. Byers’s “severely stained” copy has a spine allegedly made of sailcloth.

“This exhibition could encourage anyone to dive down any number of rabbit holes,” Buchsbaum says.

Installation view of Imaginary Books: Lost, Unfinished, and Fictive Works Found Only in Other Books at the Grolier Club, Manhattan Courtesy the Grolier Club

It is hard to resist the urge to break open the gallery cases and see what lies within the books. Doing so, though, would only reveal blank pages or the text of another book entirely. “The problem with imaginary books like this is they are magic,” Byers explains with a grin. “If you were to try to force one open, it would protect itself by turning into another book.”

But the temptation is the point. Each book brings the beholder to a liminal threshold, the space between this world and another. These moments happen in books all the time, Byers says, like “when Alice notices there’s a rabbit with a weskit, or when Lucy stumbles through the wardrobe, or when the monster’s finger twitches because it’s alive”.

In an imaginary library, visitors are invited to conjure any number of parallel universes. What if one could see the colour of magic, or step through the looking glass? What if Hemingway’s manuscripts for his first novel had not been stolen on a train in France that fateful day in 1922?

“What would it mean if we knew what Aristotle thought was funny?” Byers adds, noting that the Greek philosopher’s treatise on comedy was lost in antiquity. We may never know. “But,” he says, “I have a nice copy of it.”

Imaginary Books: Lost, Unfinished, and Fictive Works Found Only in Other Books, Grolier Club, until 15 February 2025