Keith Haring may have painted the brightly coloured mural in an Iowa City primary school’s library in a single day, but it was the culmination of years of correspondence with its students. He first visited Ernest Horn Elementary School in 1984, during a residency organised with the University of Iowa after an art teacher at Horn, Colleen Ernst, started a pen-pal exchange. Their letter-writing continued in the following years, even as Haring’s fame grew; the students sent him a VHS of themselves singing Happy Birthday, which Haring said was a favourite gift.

When he returned on 22 May 1989, Haring created the mural as a gift to the school, improvising—with input from the students—an illustrated thought bubble emerging from a book. He started with an array of shapes, lines and letters that he then transformed, such as a bent blob of turquoise becoming the rubber ring around an elephant falling from a surfboard between the letters “E” and “F”. An orange triangle became the bill of a duck, and a red circle served as the nose of a clown who is waving a flag with the image of a horn. This pictograph for “horn” is used again in Haring’s inscription at the bottom: “A book full of fun for my friends at Horn School!!”

A few months later, Haring would publicly share that he had been diagnosed with Aids, and he died at age 31 less than a year thereafter, on 16 February 1990. He had not shared his diagnosis ahead of his 1989 visit to the school, but confided in Ernst after she noticed a bruise that was actually Kaposi’s sarcoma. Horn later organised an Aids education event, and Haring wrote to the school: “It’s incredible to me that the school took the initiative to institute a discussion about Aids—mostly because of the students’ contact with (and caring for) me. It makes me proud I had the courage to talk about it in the first place. Education is the key to stopping this thing!”

On public view for the first time

Located as it is in a school in a small Midwestern city, A Book Full of Fun is one of Haring’s lesser-known murals. For the first time it is going on public view, at the University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art in an exhibition running from 4 May—coinciding with what would have been the artist’s 66th birthday—to 7 January 2025. To My Friends at Horn: Keith Haring and Iowa City contextualises the mural with works on loan from the Keith Haring Foundation, archival ephemera and photographs related to his Iowa City visits and the story of the mural’s recent conservation, which involved removing it and the entire wall it was painted on from the school.

In 2022, the Stanley was contacted by Horn about the mural ahead of a renovation project. However, at that time the museum was about to reopen after 14 years of closure following the loss of its building to a flood. “I didn’t have very much bandwidth, but I did go out and look at the mural, and I realised that it was wonderful,” Lauren Lessing, the Stanley’s director, tells The Art Newspaper. “They were about to embark on a renovation project at the school, and the mural itself was on a wall that was slated to be demolished in the summer of 2023.”

The finished mural© 2023 University of Iowa

Recognising how special the mural was, the museum partnered with the school on its conservation, with the Keith Haring Foundation and Henry Luce Foundation also joining the project. Initially, it seemed like it would be relatively straightforward to take the plywood panels that the mural was painted on off the wall, yet it soon became much more complicated. The panels were glued and bolted to the wall, and what Haring had painted on was a layer of plaster laid on top. Because these panels were so tight to the wall, cutting behind them proved impossible, and drilling from the other side of the wall revealed there was asbestos inside that required a safe abatement. Finally, both the mural and the wall were sawed out as one 1,800kg object, with the mural supported by an acrylic backing and rigid frame. The structure was carefully relocated to the museum by night, with a police escort to avoid stopping and traffic. Although there was consideration of removing the cinder blocks from the panels, ultimately they were left together.

“From a historical and curatorial point of view, we feel that the mural and the wall tell a more complete story and honour the mural’s material creation as part of the Ernest Horn Elementary School library,” explains the conservator Nina Roth-Wells.

Even after years of enjoyment by students, the mural was in good condition and did not demand extensive treatment. “Since the mural was installed in a room with no windows, there was no fading of the colours due to exposure to natural light,” Roth-Wells says. “The mural was glazed with Plexiglas that had quite a few scratches and adhesive residues, but the mural itself was pristine.”

‘An important story to tell right now’

Along with this conservation process, the Stanley’s exhibition will highlight how Haring used art for community engagement and activism. “It’s a really important story to tell right now, about the way that this little town in Iowa opened up its arms for an avant-garde graffiti artist whose work was somewhat controversial and who might not have been welcome in other places,” Lessing says. One of the works on view will be Haring’s print Ignorance = Fear, Silence = Death, made in 1989 to bring attention to the Aids crisis.

Amid tackling health issues in his life and art, Haring continued to make time to visit schools and collaborate with children; earlier in May 1989, he had painted a 488ft mural in Chicago’s Grant Park with about 500 local students. In an Iowa City Press-Citizen article on the Horn mural published on 23 May 1989, Haring said of working with young people: “For me, it’s the hardest audience. They’re the most honest… They have fresh ideas and good imaginations.”

While at the school, Haring drew portraits of the kids, took photographs and talked with them. Some of the drawings, as well as oral histories collected from the community, will be part of the Stanley’s exhibition.

Students remember him taking their artistic voices seriously

“Many of the individuals we interviewed are former students at Ernest Horn Elementary School, and they fondly recall the warmth, generosity and respect that Haring showed them,” says Diana Tuite, the exhibition’s curator. “They remember him taking their artistic voices seriously.”

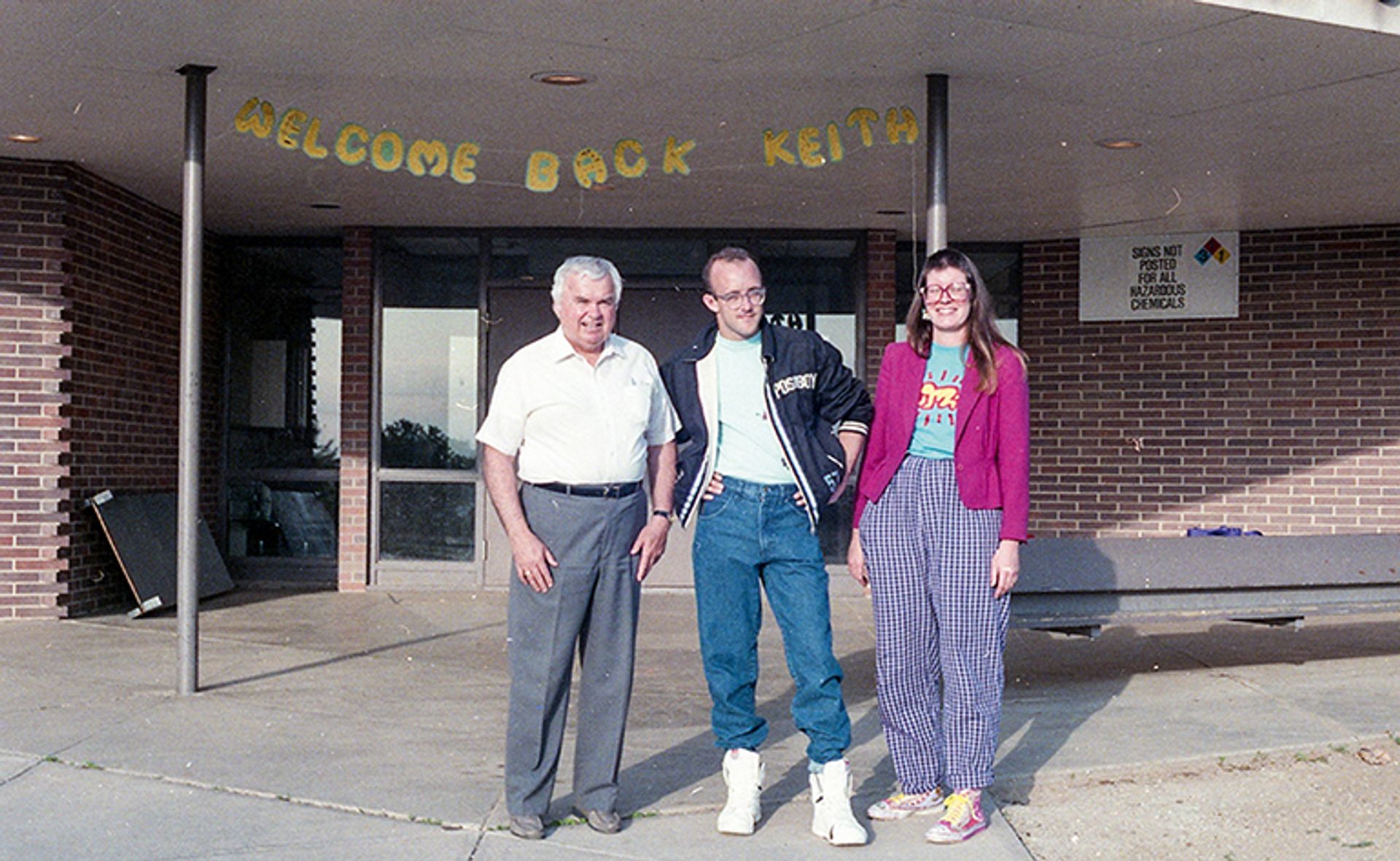

Paul E. Davis, the principal of the school, with Keith Haring and the art teacher Colleen ErnstCourtesy of Colleen Ernst

The mural will be reinstalled at the school in 2025, its scratched Plexiglas replaced with anti-reflective glazing, while new environmental controls and lighting will assure that its interconnected characters can delight students for years to come, now sharing a lesson not just of embracing creativity but of caring for art and people.

“I think it’s important to think about artwork as a legacy that we’re responsible for,” Lessing says. “We’re responsible for this mural that was left in our care by an artist whose career was far too short. So we’re its stewards. I think that’s a good thing to teach.”