In the 1920s, as Hollywood solidified the conventional grammar of narrative film and consolidated into an industry with a global reach, the Parisian modernists dabbled in cinema, exploring its potential to be nonlinear, lysergic and unprofitable. This could take the form of the startling imagery, connected only by montage, of Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s Un Chien Andalou (1929), with its juxtapositions and provocations recalling the latter’s paintings; of the tempo-shifting stop-motion and in-camera effects of René Clair’s Entr’acte (1924), commissioned by Francis Picabia to accompany a ballet with music by Erik Satie; of the rhythmic editing, fractured perspective, and overall futurist frenzy of Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy’s Ballet Mécanique (1924).

A day before its showing at the 1923 Dada-affiliated Soirée du Cœur à Barbe that was infamously disrupted by André Breton, Man Ray created his first film, the three-minute Le Retour à la raison, chiefly by sprinkling salt, pepper, pins and needles directly onto the celluloid and exposing it to light—a method he had developed in the still photos he called “Rayographs”. If the Rayographs make evident the materiality of the photographic image, Le Retour à la raison’s flickerings of light and movement also demonstrate its immateriality.

Man Ray, Emak-Bakia (Leave Me Alone), still, 1923 © Man Ray 2015 Trust / ADAGP, Paris 2023

Ray’s films have been digitally restored and open in theatres beginning today (15 May) at New York’s IFC Center, with a new score by SQÜRL, the noise-rock band composed of the film-maker Jim Jarmusch and his producer and composer Carter Logan. In Ray’s Emak-Bakia (1926), L’étoile de mer (1928) and Les mystères du château du dé (1927), experimental techniques (such as glass or gelatin filters) complement free-associative storytelling, conjuring the shapeshifting form of a dream.

“What’s most inspiring to me is his openness to play in different forms,” says Jarmusch, pointing to Ray’s practice across a wide range of media, which he sees as analogous to the collage-like assembly of his own films, with their nods to people, poems and pop songs he admires, the result a process of “collecting ideas and then assembling them rather than starting with an idea and expanding it”.

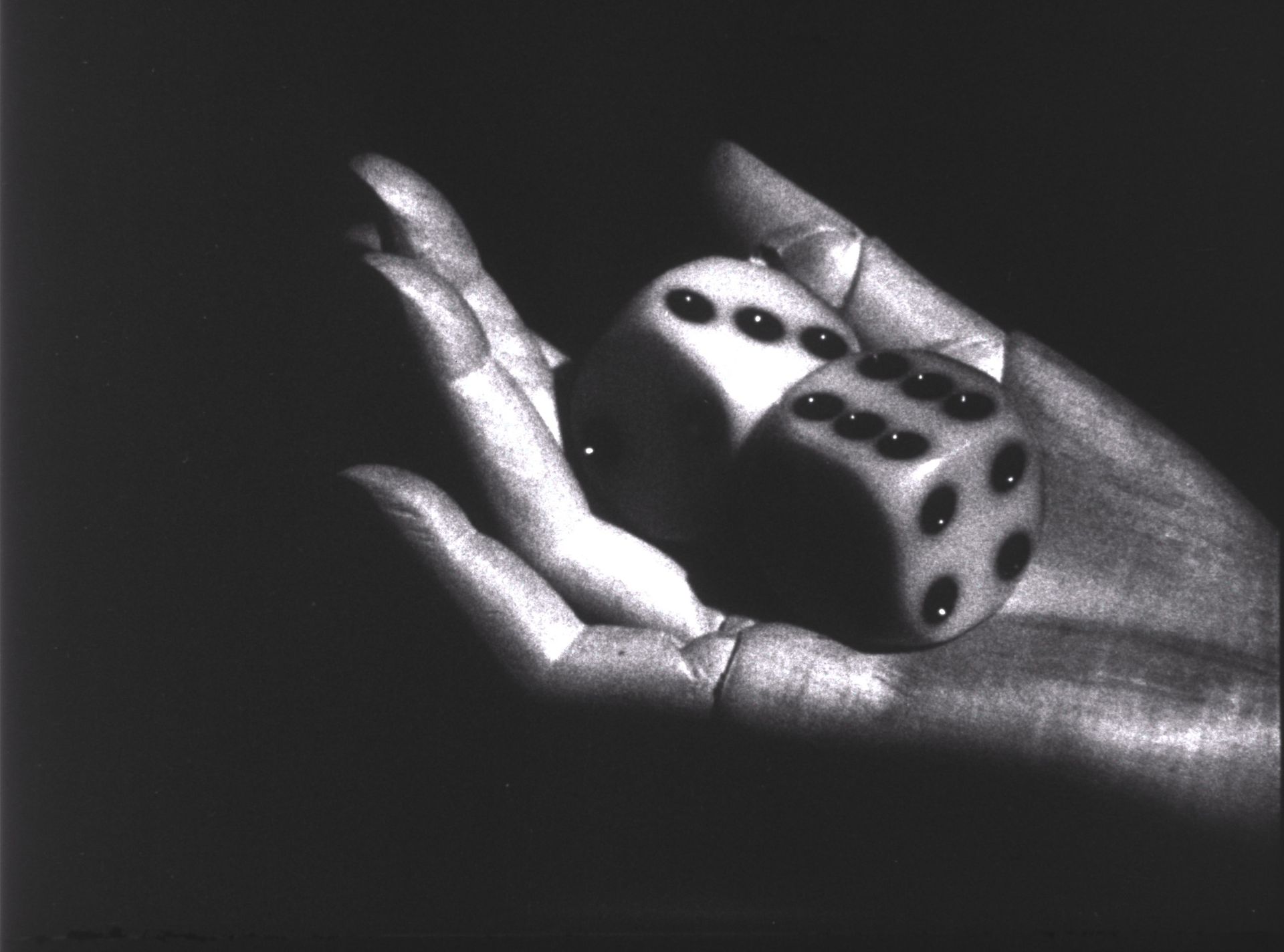

Man Ray, Les mystères du château du dé (The Mysteries of the Château of Dice), still, 1929 © Man Ray 2015 Trust / ADAGP, Paris 2023

Jarmusch and Logan have been accompanying Ray’s films at live concerts since the late 2010s; having long discussed a silent film score project, they landed on Ray after the insistent suggestion of a “teenage cinephile”, Jarmusch says, the daughter of a French colleague. Marieke Tricoire, the producer who spearheaded the restorations, had aspirations to shoot a concert film with the band, but shifted focus, she says, when she saw that the Ray footage at their shows appeared to be sourced from a 20-year-old DVD from the Centre Pompidou gift shop. When the Pompidou couldn’t turn up a better version in its own archives, early nitrate prints were found in the Cinémathèque Française and Library of Congress, though a print of Les mystères du château du dé given by Ray to the artist and patron Marie-Laure de Noailles was poorly preserved and unrecoverable, “like a block of salt”, Tricoire says.

Following their rescue from mouldering obscurity, the films remain elusive objects, as does the music. The score is semi-improvised, as a matter of principle, Logan and Jarmusch say, in deference to the “sense of play” Logan detects in the films. The fruits of Ray’s creativity extend even beyond the frame: Tricoire notes that on the first-generation print of Le Retour à la raison, the patterns left by the Rayography cover the entire strip of celluloid, surrounding the perforations. Ray “treated the camera like a toy”, Jarmusch says, a parallel to the noise-rock tendency toward “treating the instruments in not necessarily formulaic ways”.

Man Ray, Les mystères du château du dé (The Mysteries of the Château of Dice), still, 1929 © Man Ray 2015 Trust / ADAGP, Paris 2023

The music, a mantra-like swelling wave of sound, is akin to the drone-rock scores of Jarmusch films like The Limits of Control (2009) and Only Lovers Left Alive (2013), on both of which Logan served as a producer. It does not sound like the jazz or “French popular music” Ray initially suggested for his silent films, but sound and image are similarly mind-expanding. “Surrealism is about altering consciousness,” Jarmusch says, an obvious link to SQÜRL’s psychedelic vibes.

It also suggests a connection between Ray’s Paris of the 1920s and the New York of the 1970s and 80s. Several of Jarmusch’s peers, he notes, took inspiration from previous generations of French bohemians, such as Tom Verlaine, who appropriated his name from the Surrealist-progenitor poet. Both of the much-mythologised scenes were, Jarmusch feels, “vibrating with experimentalism”, evident in the fertile cross-pollination of music, film, literature and visual art, as well as in “anti-mainstream, anti-bourgeois attitudes”. The punks and the Surrealists alike, says Logan, avoided specialisation and professionalism, choosing instead to “live on the margins of culture and therefore on the cutting edge”.

Watch the trailer for Man Ray: Return to Reason:

Man Ray: Return to Reason, IFC Center, New York, opens 15 May