Since the invention of the internet, one of its gifts to civilization has been a new economy of language. Over the last two decades, Twitter (currently known as X) has turned all of us into haiku masters, wherein brevity and wit became social currency. Despite predating Twitter by nearly 30 years, Jenny Holzer’s text-oriented practice is also fundamentally reliant on said currency. Evaluating the 73-year-old Holzer in a post-internet world is therefore a precarious ordeal. Her latest exhibition at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Light Line, is unfortunately a half-hearted monument to pithiness, encumbered by an age when cynical brevity no longer moves us, regardless of how it is presented.

This conundrum is somewhat reminiscent of Wolfgang Tillmans’s 2022-23 Museum of Modern Art exhibition To look without fear. Instagram had been a part of our lives for more than a decade by the time the show opened, and Tillmans’s once unique style of photography had not only been co-opted but became the aesthetic norm for sharing visual updates of one’s life. As a result, images that once may have read as groundbreaking in their rejection of classical composition and formalist teachings were now everyday to the point of inconsequential.

If the quippy and cynical modern-art adage of “I could do that” versus “but you didn’t” no longer holds true—if we are all, in fact, “doing it”—can artists like Holzer and Tillmans survive the scrutiny that their institutional exaltation invites? Our ever-refreshing social-media timelines actively present us with content that effortlessly competes with the aesthetics, if not the sentiment, of Boomer-era artists. The aphoristic prowess of Holzer is now shared by teenagers and Millennials alike.

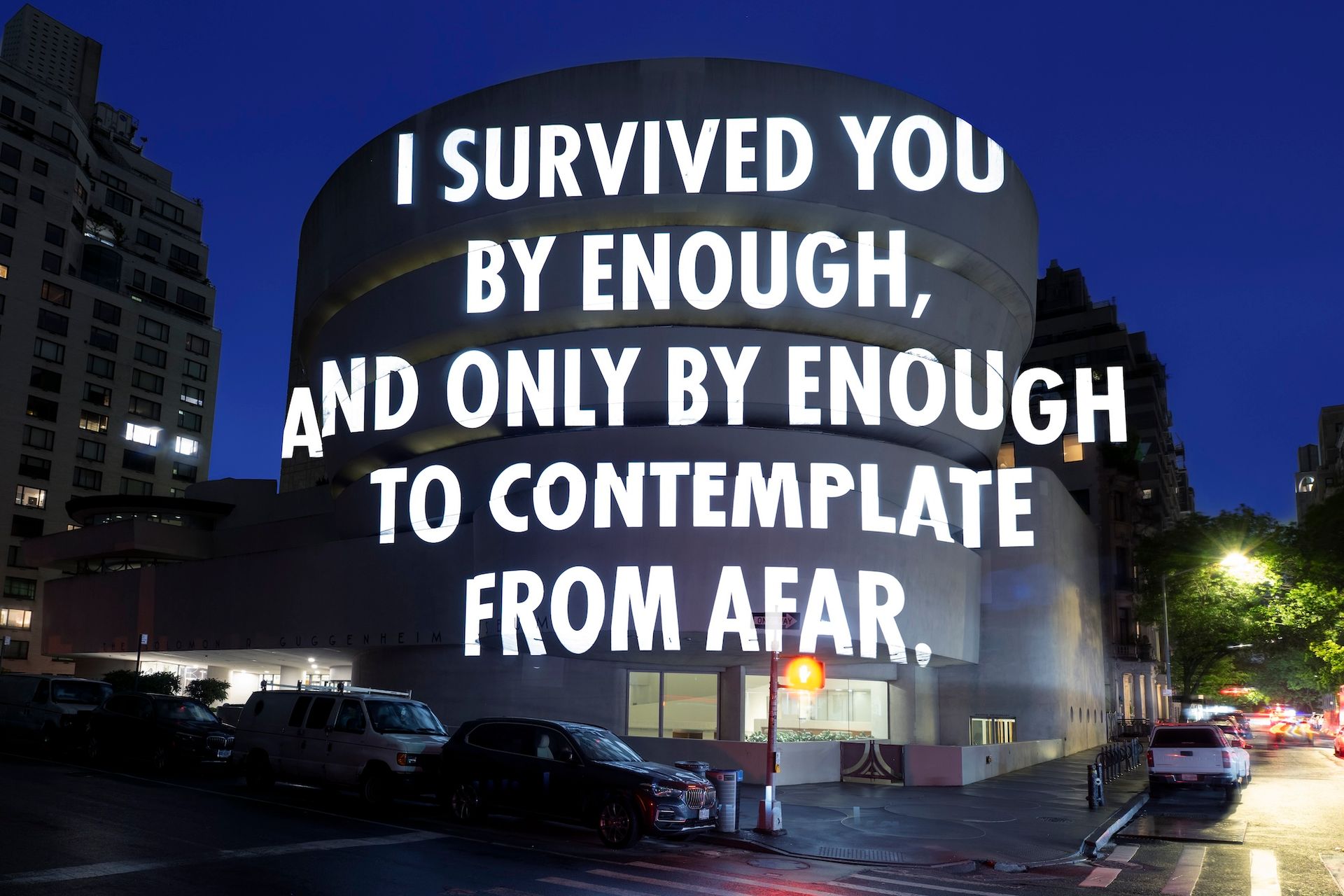

2024: Installation view of Jenny Holzer: Light Line, 17 May–29 September 2024, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © 2024 Jenny Holzer, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Filip Wolak

Presenting a Holzer show 35 years after her Guggenheim debut could have been a fantastic opportunity to introduce a younger generation to the history of political, text-based and digital works of art. But rather than functioning as an educational exercise, the exhibition’s sparseness and cynicism can feel, at times, simultaneously half-hearted and overbearing.

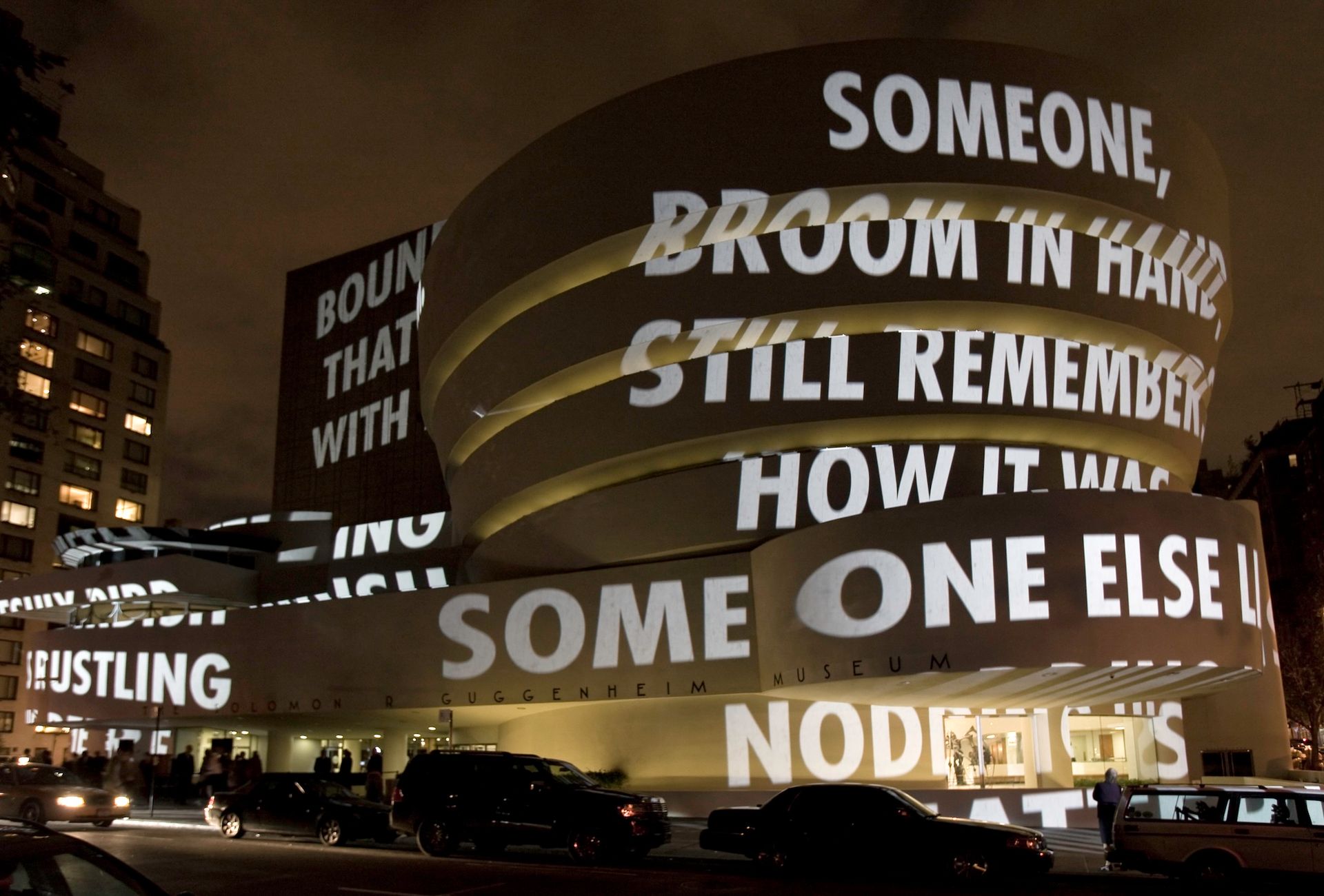

The star of Light Line is the resurrected LED work Installation for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1989/2024). Spanning the iconic spiral of the museum, the lengthy screen (nearly twice the length of the 1989 installation, which only went up three storeys out of the six available) was once revelatory but now showcases phrases we are all too familiar with, only featuring better graphics. In this iteration of the piece, once again we are presented with poetic and oftentimes disjointed phrases that slide upwards in the museum’s rotunda. “You are the one” and “You are the one who did this to me” crawl after one another to keep first-time readers in a perpetual state of apprehension, unable to determine if they can trust the romanticism that is so often both deceptive and short-lived in Holzer’s works.

The text crawls are divided into several sequences marked by a brief dark pause during which the screens do not display anything, and when new text flows there is a different typeface and animation style. The most pixelated of typefaces presents some of the more ominous phrases: “I tease you” is followed by “I tickle you”, then “I wait for you” and “I scan you”, progressively becoming more predatory but also moving quickly enough to deny visitors a chance to linger on individual sentiments for too long. Although the previous installation also had shifts in typefaces, this iteration creates some degree of confusion. The exhibition text also mentions that Holzer used artificial intelligence (AI) in this new version.

1989: Jenny Holzer, Untitled (Selections from Truisms, Inflammatory Essays, The Living Series, The Survival Series, Under a Rock, Laments, and Child Text), 1989. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © 2023 Jenny Holzer. Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

For anyone unfamiliar with Holzer’s iconic phrases, it is natural to think that some of the text might be AI-generated, or that the pixelated typeface, for example, is meant to signify AI responding to her sentences. It is a letdown to discover that several AI tools—ChatGPT, Dall-E and Runway—were used only to create some of the decorative animations behind the words. Given the extraordinary possibilities Holzer’s work holds for AI experimentation and dialogue, these cosmetic interventions are so cursory and secondary to the text that one wonders why she went through the exercise of using AI at all.

While the museum statement heralds Installation for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum as a significant archival project that involved reverse-engineering the LED screens used in 1989, the entire activity seems to eschew any practical consideration in favour of laborious reverence… or perhaps a kind of insistence on authenticity. Like a VHS-tape filter on a TikTok video, despite mimicking the form of the older installation, the new and improved LED screens feel lacklustre in their nostalgia. In 1989, using inherently commercial LED-screen technology to reimagine the Guggenheim’s exhibition capabilities was refreshing and innovative. This time around, the hardware is neither vintage enough to be quaint nor cutting-edge enough to be a commentary on technology or capitalism today.

While the digital text crawl dominates the exhibition, it is restrained in its political commentary, unlike the rest of the pieces in Light Line. Traversed from the ground floor up, the show leads the viewer through a colourful side room containing an installation aptly titled the beginning (2024), with repeated versions of Holzer’s Inflammatory Essays series (1979-82) printed on neon-coloured posters plastered all the way up to the ceiling. What the wall text refers to as a collaboration on the installation feels more like an intervention, with additional text graffitied over the posters in large, old-school graffiti font by Holzer’s collaborator and friend Lee Quiñones.

2024: Installation view of Jenny Holzer: Light Line, 17 May–29 September 2024, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © 2024 Jenny Holzer, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Ariel Ione Williams and David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

The collaboration/intervention contains quotes such as “I JUST STOOD THERE FOR AN HOUR SCREAMING MY CHILDREN’S NAMES”, and the spectres of present-day conflicts linger in the room, though something about deadpan graffiti feels rather callous. Despite the iconic typeface that adorned many a subway car in the 1980s, in this very bright, neon-coloured room in the Guggenheim, the conceit is thin.

The same hall contains Holzer’s ubiquitous benches featuring text, some of which are part of the LED-screen text crawl, although the sheer amount of colourful neon pages adorning the walls does not allow for the comparably more poetic marble benches to shine.

Meanwhile, in Cursed (2022)—a collection of tweets by the former president Donald Trump—each tweet is stamped on metals such as lead and copper, thus memorialising a form of digital self-expression that is paradoxically fleeting yet archival. Featuring Trump’s tweets years before, leading up to and during the 6 January insurrection, the installation can be described as an exercise in posterity, if not accountability. Given Holzer’s continued commentary on fascistic rule and abuse of power, her focus on the former president comes as no surprise. However, there is something to be said about immortalising Trump’s presumably unplanned online vitriol—the same vitriol that has garnered him much of his power today.

2024: Jenny Holzer, For the Guggenheim, 2008/2024. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © 2024 Jenny Holzer, Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Filip Wolak

There are several additional benches on the way up the rotunda, including some that have seemingly been smashed, possibly a demonstration of the artist’s own impermanence. One of the more tender stone pieces from Holzer’s bench era, a sarcophagus made from Nubian black granite, Lament: The new disease came… (1988-89)—about the Aids crisis—is presented intact, almost as if to signify that some things are sacred. Or, at the very least, exempt from destruction. Even if said destruction is a meditation on mortality.

The subsequent works include large-scale paintings of redacted and declassified documents, such as an FBI surveillance report of the artist Alice Neel and her suspected Communist affiliations, as well as internal memos and emails from US military officials on the use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. Enlarged paintings of clip-art-esque infographics on war tactics follow, including one depicting plans to invade Iraq.

The exhibition culminates in a series of large-scale, sparkling canvases created using a variety of gold, palladium and platinum leaves. The newest works presented in the show, they may also be the most intriguing pieces, despite their latent Lalique aesthetic. One such canvas reads “SLAUGHTERBOTS” (SLAUGHTERBOTS, 2024), featuring a minimalist rendering of an abstract M above a shorter W shape, evoking architectural drawings of brutalist structures. This piece incorporates AI as well: the shape is conjured using Dall-E, which was fed the word slaughterbots. How such minimal, asymmetrical bots will come to exist, and how they may be used as weapons, is not revealed.

2008: Jenny Holzer, For the Guggenheim, 2008. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York © 2024 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photo: Kristopher McKay © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

That the work is neighboured by a similar piece featuring a painted gold-leaf keyhole, with the phrase “The distant future is visible to the naked eye through the keyhole of history” (The distant future, 2024) overlaid on top of it, is rather unfortunate and heavy-handed. It reduces the politics of the exhibition into a cynical warning of Terminators to come. Given Holzer’s proclivity for cynicism, such an ominous sentiment is perhaps to be expected. But the accidental poetry of some of the redacted declassified documents, and the intentional poetry of Holzer herself, suddenly becomes fodder for a looming future filled with slaughterbots.

Holzer’s recent work is a clear indication that she recognises the post-internet landscape she treads. What is perplexing is her decision to combat the transience of social media by quoting traces of it, either anonymously or sometimes with too much emphasis on one particular author. Holzer’s pithiness may have inspired some of the economy of language we all navigate on the web today. But her new works in Light Line betray a thirst for a kind of political accountability in the face of social-media timelines and news feeds that refresh faster than her LED text crawls. It is a kind of reverse damnatio memoriae. A fixation on posterity that younger denizens of the web may not share.

Jenny Holzer: Light Line, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, until 29 September 2024