Artist, curator, gallery founder and peace activist Chaim Peri has died in Hamas captivity in Gaza, after continuous appeals for his release since his abduction from his home in Kibbutz Nir Oz on 7 October 2023. He was 79.

A video released by Hamas in December confirmed that hostages Peri, Amiram Cooper (84) and Yoram Metzger (80) were still alive, but on Monday the Israeli military announced the deaths of all three (along with one other hostage, Nadav Popplewell, aged 51).

Peri is survived by his wife Osnat, whose life he saved by surrendering to terrorists that invaded their home. He is also survived by five children and 13 grandchildren (Mai, Daphne, Itai, Lia, Noy, Gili, Naomi, Ella, Daria, Neta, Ofir, Ayana, and Arbel). Peri was one of 77 hostages taken from Nir Oz, a kibbutz that had roughly 400 residents before 7 October. This announcement brings the number of murdered Nir Oz residents to 55; 22 of the hostages from Nir Oz remain in captivity and 40 were released in an exchange deal last November. Around 1,200 people were killed in Hamas’s terror attacks in Israel on 7 October, and around 250 people were taken hostage. More than 35,000 Palestinians have been killed in the Israeli military’s ongoing aerial and ground campaign in Gaza, according to health authorities there.

A self-taught artist who sketched, sculpted, filmed and wrote screenplays and children’s books, Peri was primarily known in the Israeli cultural community as the founder and curator of The White House gallery in the fields between Nir Oz and neighbouring Kibbutz Nirim.

Born in Givatayim, Peri moved to Nir Oz when he was 18 and, among other roles, worked as a metalworker. Like several other residents of the region (including Oded Lifshitz, who remains in Hamas captivity), Peri volunteered with The Road to Recovery—a non-profit group of Israeli volunteers driving and accompanying Palestinians from checkpoints in Gaza and the West Bank to receive medical care in Israel.

Sculptures by Chaim Peri outside The White House gallery Courtesy of The White House gallery

Peri founded The White House gallery in 1999 as a passion project, in a deserted building with a complex history. The modest rectangular structure was the last remnant of an Ottoman-era Palestinian village, later used by British and Israeli military before being abandoned. Peri renovated the building himself, without external funding. The gallery was floorless when Peri opened its inaugural exhibition; over time he added floor tiles, fixed the walls, installed windows, doors, shutters and lighting (the gallery still lacks water and electricity, but Peri brought a generator during visiting hours).

The space was intentionally raw and remote, encouraging artists to be experimental. “It was a place that was really off the grid,” says Avi Lubin, the chief curator of the Mishkan Museum of Art, who met Peri at The White House in 2017. “On the one hand, he hosted tons of active artists. And on the other hand, in terms of location, it’s in the middle of nowhere—it’s not in a town, it’s not easy to get to, especially without a car—but his hospitality was very enabling and free.”

Peri curated a broad range of exhibitions. “He always made an effort to have diverse exhibitions,” says artist and illustrator Ophra Eyal, who received her first-ever solo exhibition opportunity from Peri and showed twice at The White House. “It was important to him to show work by women and men, Bedouins and Arabs.”

Peri encouraged artists to show work they wouldn’t or couldn’t exhibit elsewhere, and past exhibitors at The White House include Pavel Wolberg, Assi Meshullam, Israel Kabala, Moshe Tarka, David Gerstein and Liron Lupo.

An amateur sculptor with works scattered around Nir Oz, Peri also established a sculpture garden outside the gallery with his own sculptures and others by Menashe Kadishman, Dov Heller (who also illustrated a children’s book written by Peri), Noam Rabinovich, Ilan Gelber, Varda Givoli and the Kafr Qara-based artist Rania Akil, among others.

Akil’s sculpture Borderless Sun, Sky, and Water is in the garden, and she also exhibited inside the gallery. “It was more than an encounter between an artist and a curator, but rather with a person with passion, principles and purpose, and most importantly a big heart,” Akil wrote about Peri in November on the gallery’s Facebook page (the off-the-grid venue’s only online presence). “I’m proud of the two solo exhibitions that Chaim curated, which created space for the Palestinian story.”

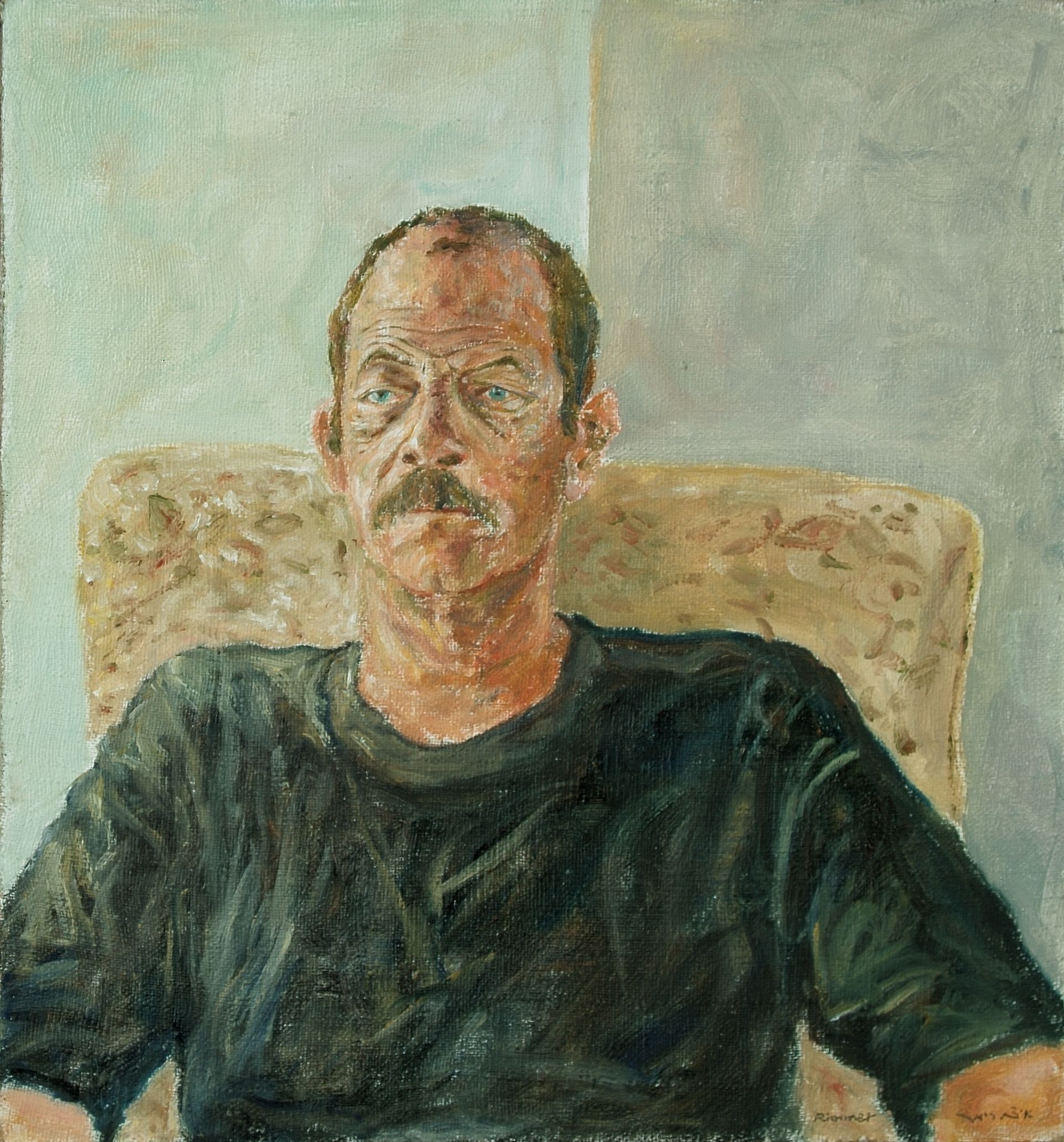

Itzu Rimmer, Chaim Peri, 2007 Courtesy the artist

Akil worked on Borderless Sun, Sky, and Water over several months, partially during the 2014 Israel-Hamas conflict. “Even though he was recovering from heart surgery, he didn’t want to leave me alone in the desert,” wrote Akil, “and hosted me in his home until I finished the sculpture.”

Peri has been honoured by Israel’s cultural community since 7 October. Feature articles about him appeared in the newspaper Haaretz and the arts magazine Portfolio, and the Givat Haviva Shared Art Center initiated a social media campaign encouraging artists to share their memories of Peri. His daughter-in-law, the photographer Sharon Derhy, began a project in December recreating family photos of hostages after their abduction. Peri’s instalment shows him reading on his porch with his son, Lior, in 2022; then Lior alone there in October 2023, with a hostage poster on the door.

A group exhibition focused on two art galleries operating along the Gaza-Israel border—Be’eri Gallery and The White Gallery—opened in Tel Aviv’s Sarona Azrieli last November. Another group show titled Draw me Hope that opened at Herzlia’s TEO center in March included one of Peri’s sculptures.

And Eyal, who was collaborating with Peri to illustrate his autobiographical children’s book about looking for the moon with his granddaughter, Ella, completed it during his captivity and released it in April to mark his 80th birthday. “I hear him reading when I read it,” Eyal says of the book, Yarena. “He had a very strong flavour and personality, and in everything that he touched his special personality comes through—with charm and humour, human warmth, soul, intelligence, nonconformism and rebelliousness.”

Ella’s impatient search for a missing moon in Yarena mirrors the agonising wait for Peri. Eyal drew Peri as the grandfather in the book, using family photos in lieu of sketching him in person. In one spread, Ella and her grandfather fail to find the moon. “With a bit of patience,” Peri wrote in Yarena, “on our next walk we’ll see her shining in all her brilliance.”

“I’m still speaking about him in the present tense, because it’s hard for me to accept that he’s gone,” Eyal says. “Chaim was a very beloved person, who was also very open and accepting. A person with a lot of love to offer, and he also received a lot of love.”