Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, an artist and activist who was a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, died on 24 January after a long battle with pancreatic cancer. Her gallery in New York, Garth Greenan Gallery, confirmed the news of her death. She was 85.

Smith’s work often took on, critiqued, ridiculed and subverted the imagery of mainstream Americana as well as the US Modern art orthodoxy across paintings, sculptures, prints and more. She made works reminiscent of Andy Warhol that riffed on advertising iconography, intricate collages and transfers evocative of Robert Rauschenberg, and paintings based on the flag and map of the US that interpollated Jasper Johns. Throughout she injected her own imagery and commentary—sometimes playful, sometimes arrestingly bleak—about the darker aspects of US history, especially the systematic killing, dispossession and stereotyping of Native Americans.

At the time of her 2023 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art—the first retrospective devoted to a Native American artist in the museum’s history, curated by Laura Phipps—Smith told The Art Newspaper of her map paintings: “I began with the premise that the map didn’t belong to Jasper Johns, the map was an abstract image of stolen land in this country, so how could I turn the map into a new story?”

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, I See Red: Target, 1992. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC Courtesy of the estate of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

That exhibition (which subsequently travelled to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Texas and the Seattle Art Museum) came amid a wave of long-overdue recognition, though Smith had been showing work and championing that of other Native American artists for decades. The same year, she curated The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans, the first-ever show at the National Gallery of Art (NGA) in Washington, DC, to be curated by an artist. In 2020, Smith’s towering mixed-media canvas I See Red: Target (1992) became the first painting by a Native American artist the NGA had ever acquired. Prior to her death, Smith had been working on her next major curatorial effort, Indigenous Identities: Here, Now & Always, which opens at Rutgers University’s Zimmerli Art Museum later this week (1 February-21 December).

Smith reflected on the recent reckoning with systemic racism at US museums at the time of her Whitney retrospective. “The most important thing that happened was Black Lives Matter, George Floyd and Standing Rock—that began to shake some of the institutions in this country and rattle their cages,” she said. “It was clear that there was an underbelly to this country that wasn’t happy with the way things are.”

Throughout her work, Smith resisted Euro-American narratives and stereotypes about Native Americans, often doing so through satire and humour. Her 1994 lithograph Modern Times, for instance, appropriated an industrial apple grower’s logo—an icon of a generic Indigenous figure wearing a colourful, feathered headdress—and affixed it to the body of a man in a business suit. The resulting mashup slyly asserts that Indigenous people are complex and contemporary individuals living today, not static symbols of history.

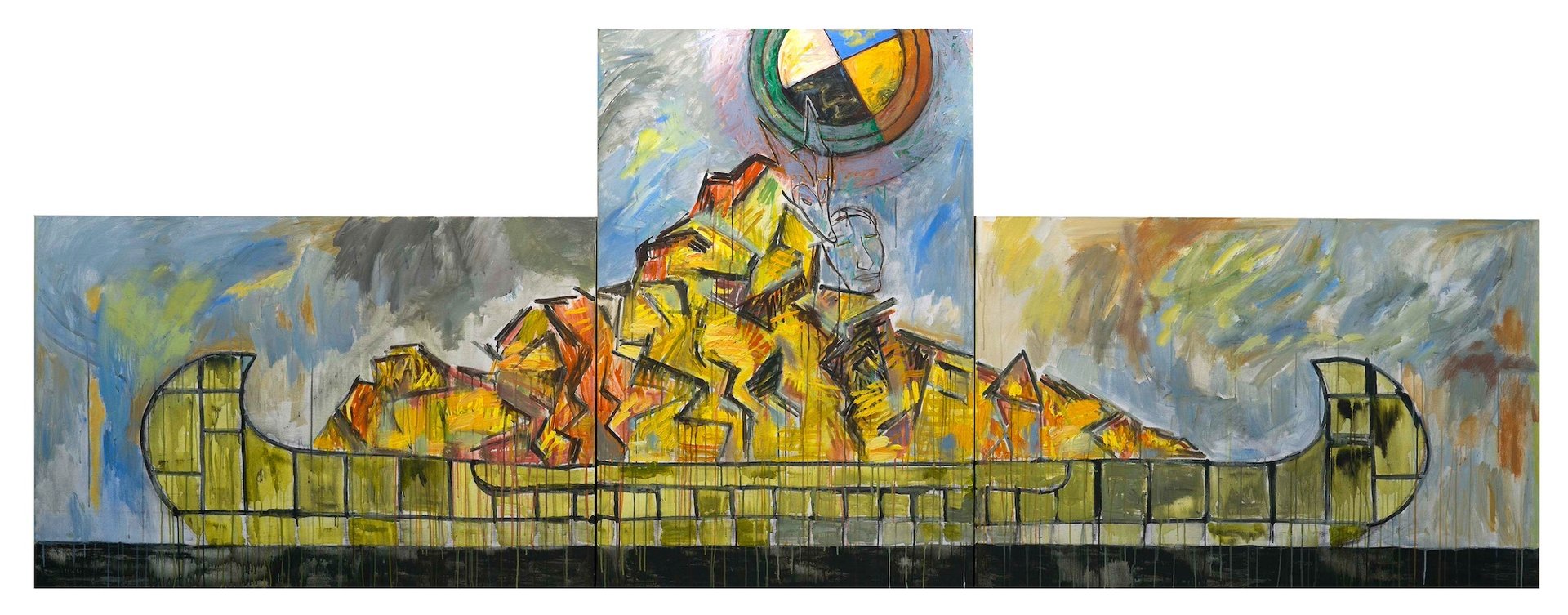

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Trade Canoe: El Dorado, 2024 Courtesy of the estate of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

“Jaune’s loss is deeply felt and indescribably significant. She was a beloved mentor and friend and truly one of the most thoughtful and talented human beings I have encountered,” Garth Greenan, her longtime dealer, said in a statement. “She was one of the very brightest lights in contemporary American art. If a more generous person ever existed, I’d like to meet them.”

Born in 1940 at the St Ignatius Indian Mission in Montana, Smith spent the latter part of her childhood near Tacoma, Washington, before earning a bachelor’s degree in art education from Framingham State College in Massachusetts in 1976. She then moved to Albuquerque to pursue a degree in Native American studies at the University of New Mexico, but was not accepted to the programme. Instead, she enrolled in the university’s art programme, graduating with a master’s degree in 1980. Around the same time, she became involved with the Tamarind Institute, a renowned lithography studio that is now part of the University of New Mexico. In 2008, the university gave her an honorary doctorate.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, I See Red: Indian Map, 1992. Glenstone Foundation Courtesy of the estate of the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

In an interview for the Whitney Museum retrospective’s catalogue with the curator and art historian Lowery Stokes Sims, Smith reflected on an influential series she made in response to the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the Americas.

“In 1992 I created a series of works titled I See Red to remind viewers that Native Americans are still alive,” she told Sims. “This is always my interest, even though I’m collaging things like old photographs and 1930s fruit labels on the surfaces of these paintings. But then there are also newspaper articles about current events. So there’s a historical continuity from something in the past, up to the present.”