Photographs of nude men by George Platt Lynes (1907-1955), the subject of a new documentary film, will be known to some and new to many. Lynes kept them secret during his lifetime.

In his twenties, after a trip to Paris, Lynes dropped out of Yale University and assembled a corps of connected friends who included Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas and Jean Cocteau. He figured for years in a love triangle with the book designer Monroe Wheeler (later of the Museum of Modern Art) and the then-famous author Glenway Wescott.

Lynes’s pictures and the people in them are the focus of director Sam Shahid’s Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes, which opens in select theatres and on Amazon and Apple TV on Friday (31 May).

Male nude by George Platt Lynes. Courtesy of A Precious Few LLC

The description “hidden”, when applied to Lynes, is a relative term. A handsome aspiring writer, Lynes was well-known in literary social circles and much-photographed. When he failed to write anything of note, despite a sex life that could have filled volumes, he took up photography instead, first focusing on his celebrity acquaintances. Those sitters accounted for his initial sales, but his elegance in posing and lighting them helped him build a clientele of new subjects, many of them rich Americans in Paris and New York.

In 1932, Lynes had a one-man show at Leggett Gallery in New York. Later that year in New York, the dealer Julien Levy paired his work with photographs by Walker Evans. That same year, in a jumble of a show at MoMA of American aspirants to commissions at Rockefeller Center, he made a “photo-mural” of architectural shapes and two classically inspired heads.

One person who noticed was Alfred Barr, the young founding director of MoMA. In Barr’s massive 1936 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism—a broad selection of applied Surrealism—Lynes’s photo-montage The Sleepwalker (1935) showed a naked sleeping man on a platform above a nude male figure seen from behind from the waist down, a clear enough code for some Lynes themes. Lynes became a regular photographer for fashion designers and the official photographer for the new American Ballet Company under George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein, an old schoolmate.

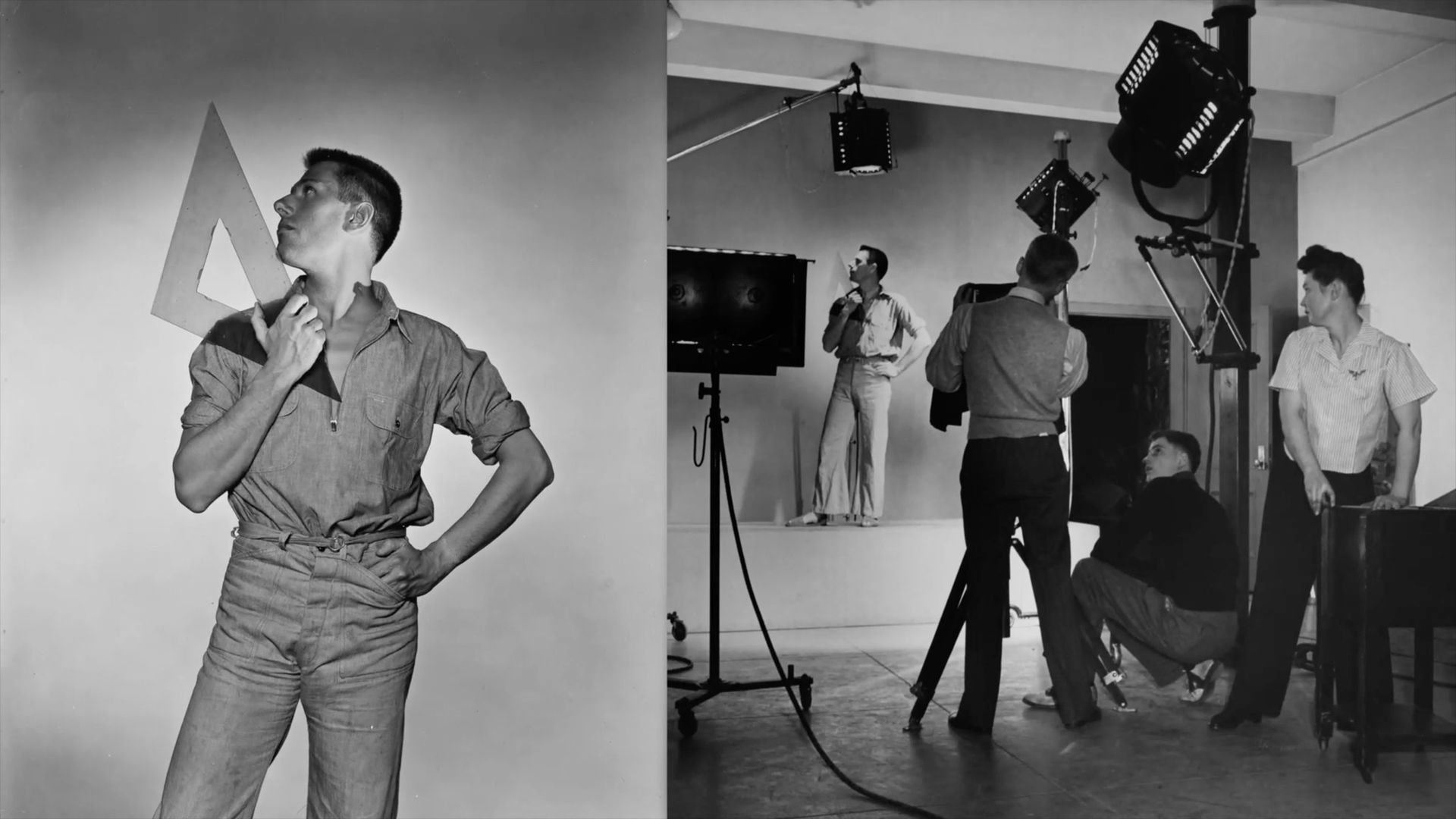

George Platt Lynes in the studio photographing the artist Paul Cadmus. Courtesy of A Precious Few LLC

Alongside businesses in portraiture and fashion, Lynes photographed nude men, chosen from the theatre, the ballet and his ever-growing circle of young attractive friends. He never sold or showed those pictures publicly or sent them through the mail, which would have been a crime under the US laws of the day. “He couldn’t do that at the time, in the 1920s, 30s, 40s and 50s, there was no way. George only shared those photographs with his friends,” says Shahid, a longtime art director in fashion and magazines, who spent ten years making the film.

Lynes lived lavishly, while his success lasted. After the Second World War, deep in debt, he watched as a new fashion photographer, Richard Avedon, made his carefully constructed images seem outmoded. It didn’t help that the wider art world was in thrall to hyper-masculine Abstract Expressionists. Before dying broke at 48, “he burned all his fashion pictures”, says Shahid.

Lynes donated his male nudes to the Kinsey Institute at the University of Indiana, which studies human sexuality of all sorts and peculiarities. Alfred Kinsey, its director, had witnessed some of the sex couplings that Lynes photographed and interviewed participants as part of his research.

Male nudes by George Platt Lynes. Courtesy of A Precious Few LLC

“He was interested in Kinsey, to protect the work,” Shahid says. Pictures left in his home and studio were sold. An eventual buyer of nudes was Frederick Koch, an heir to one of America’s largest fortunes, whose family funds right-wing causes in the US.

Koch, more liberal than his libertarian brothers, “did not want the world to know that he had the biggest homoerotic collection”, Shahid says. “He would never show it and never speak of it.” In the documentary, Shahid’s camera moves among files of Lynes’s images acquired by Koch and now held by a foundation established in his name.

Shahid’s documentary does not push heavily for Lynes’s status—though some have cast him as a pre-cursor to Robert Mapplethorpe. “I want him to be honoured for what he is as an artist and the fact that he was proud and not ashamed for being who he was—gay—and that he was attracted to men, and showed them in the best way, very artistically, but beautifully,” Shahid says. “I want him to be known like Bruce Weber and Herb Ritts were known, and Mapplethorpe and Jean Cocteau.”

Watch the trailer for Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes:

Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes opens in select theatres and on Amazon and Apple TV on 31 May