On 13 October, less than two weeks after Mexico’s first female president Claudia Sheinbaum was inaugurated—a moment billed as signalling tiempo de mujeres, the country’s “woman’s hour”—pandemonium broke out at Mexico City’s Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (Muac). Armed with a megaphone and spray paint, a group of activists tagged the entrance and lobby to protest the work Extract of a failed project (2011-24) by the Argentinian artist Ana Gallardo. Their claim—circulated and amplified for weeks on social media before the acts of vandalism—was that the piece revictimised elderly sex workers living in a local care home. Five months prior, animal rights activists had protested at the entrance of the Museo Tamayo against the performance piece Tragedy (2011) by the Danish artist Nina Beier, where five dogs played dead on piles of Persian rugs. The furore on social media—with even the mayor weighing in—led the local zoning and environmental code office to begin a formal investigation against the museum for using live animals as entertainment.

Although they occurred months apart, these episodes at two of Mexico City’s leading contemporary art museums have much in common: both were responses to solo shows by foreign women artists (Gallardo has divided her time between Mexico City and Buenos Aires since the late 1980s), both claimed the artists were trafficking in exploitation and both museums chose to resolve their respective crises through censorship. On 15 October, the Muac announced it was removing the offending work from Gallardo’s show (Here Trembled A Delirium, until 13 December), while it took the Museo Tamayo only three days from the public inauguration of Beier’s exhibition, Casts (23 May-29 September), to cancel all further performances of Tragedy, originally scheduled for the full run of the show. Together, the events evidence two worrying trends in Mexico City’s arts scene: an ugly disparagement of foreign women artists and curatorial cluelessness towards institutional disaffection.

Graffiti on a public sculpture outside the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo in protest of a work inside by Ana Gallardo Photo courtesy Ximena Apisdorf

The scorn directed towards Beier was primarily on social media, with users responding to the controversy with phrases like “white people being white” and “#ninabeier go back to your country please!” The derision towards Gallardo grew more extreme, including the phrase “blanKKKa privilegiada” (“privileged whitey” styled to allude to the Ku Klux Klan) spray painted at the Muac’s entrance. What exactly is happening in museums in Mexico City to normalise such xenophobic and misogynistic bigotry as part of the public response to shows by two internationally recognised artists?

Much of the answer has to do with the failure of local museum leaders to act as mediators between artists and their publics. For decades now, curators in Mexico have operated on the assumption that Mexico City belongs to the cosmopolitan art circuit extending from New York to London, Berlin and Los Angeles. Their work has been intended for a cultivated, art-going public, brought up on a diet of artists who flourished in the 1990s and early 2000s and catapulted Mexico City into the international scene, artists like Santiago Sierra, Daniela Rossell, Minerva Cuevas, Yoshua Okón and Miguel Calderón. The international attention heaped on these artists stirred up a sense of total creative freedom that they often tested—sometimes to the limit—by toeing the boundaries of moral ambiguity and ethically questionable practices. The director of the Museo Tamayo, Magalí Arriola, came of age as a curator with these artists, as did Cuauhtémoc Medina, the chief curator at the Muac. Both were left holding the bag when things went sour this year.

Portesters outside the Museo Tamayo rallied against Tragedy (2011), a piece by the Danish artist Nina Beier, where five dogs played dead on piles of Persian carpets Photo courtesy Ximena Apisdorf

These two shows originated in part abroad: Casts was curated by the Hammer Museum’s Aram Moshayedi, who is currently serving as curator-in-residence at the Tamayo; and Here Trembled A Delirium was curated by Alfredo Aracil and Violeta Janeiro of Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo in Madrid. Neither Mexican museum seems to have probed the moral—and in the Tamayo’s case, the legal—consequences of showing works that might provoke social justice crusaders, who honed their attacks against institutions like museums for the past six years during Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s (Amlo) presidency.

To be sure, contemporary art exhibitions triggered scandals in Mexico City before Amlo. What is different now is that local museums are programming for a society where urgent and legitimate efforts to expose gender issues, inequality and abuse have become conflated with a polarising discourse associated with the ruling Morena political party. Although it calls itself left-wing and progressive, Morena is stridently nationalist and has stoked a conservative divide-and-conquer climate where society is split between fifís—nabobs—and chairos—plebs. In such reductive social calculations, art museums unsurprisingly end up branded as fifí, institutions of and for the rich and privileged. Morena uses its formidable social media machine to pummel political adversaries and push divisive propaganda. Cancellation has become the weapon of choice to intimidate whoever dares oppose the party’s agenda or who simply holds a differing opinion from its crushing majority.

Installation view of Tragedy (2011) by the Danish artist Nina Beier at Museo Tamayo Photo courtesy Ximena Apisdorf

In this schismatic landscape, art from just 13 years ago can become unpresentable, as illustrated by the museums’ censorship (not entirely coincidentally, both Beier and Gallardo’s pieces date from 2011). Before the social media maelstroms forced these reckonings, neither museum’s leaders seem to have grasped that art now circulates beyond the gallery in the form of photographs and videos shared online, and that the curator’s role as interpreter of the art presented in the galleries can instantaneously be rendered null and void. Social media users rarely read the wall labels—they read the comments. Most museums know this and their social media staff and marketing campaigns take it into account. But the Muac and Museo Tamayo had seemingly not anticipated what this dynamic might mean for their exhibition programming or the public reception of works that called elderly sex workers “old street whores” (Gallardo) and immobilised dogs on command in a city where strays are ubiquitous and animal abuse is rampant (Beier). Decontextualised on social media, the provocative works were easily vilified as instances of oppression and abuse, fuelling the fifí/chairo dualism.

The personal persecution of Gallardo and Beier is a direct result of this new social environment. If the art world used to inveigh against artists representing the heteropatriarchy, online witch hunts now see wickedness in daring to make work that probes at social ills that do not personally affect the maker, earning them the label of “exploiter”. This sort of accusation has recently extended beyond white, foreign artists: it arose this month against Teresa Margolles, a Mexican artist whose work A Thousand Times in an Instant is currently installed on the Fourth Plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square. Margolles, who lives in Madrid, organised a meeting at the Center of the Image in Mexico City with trans women activists who participated in the project, where a number of them accused her of capitalising on trans women’s murders with the commission.

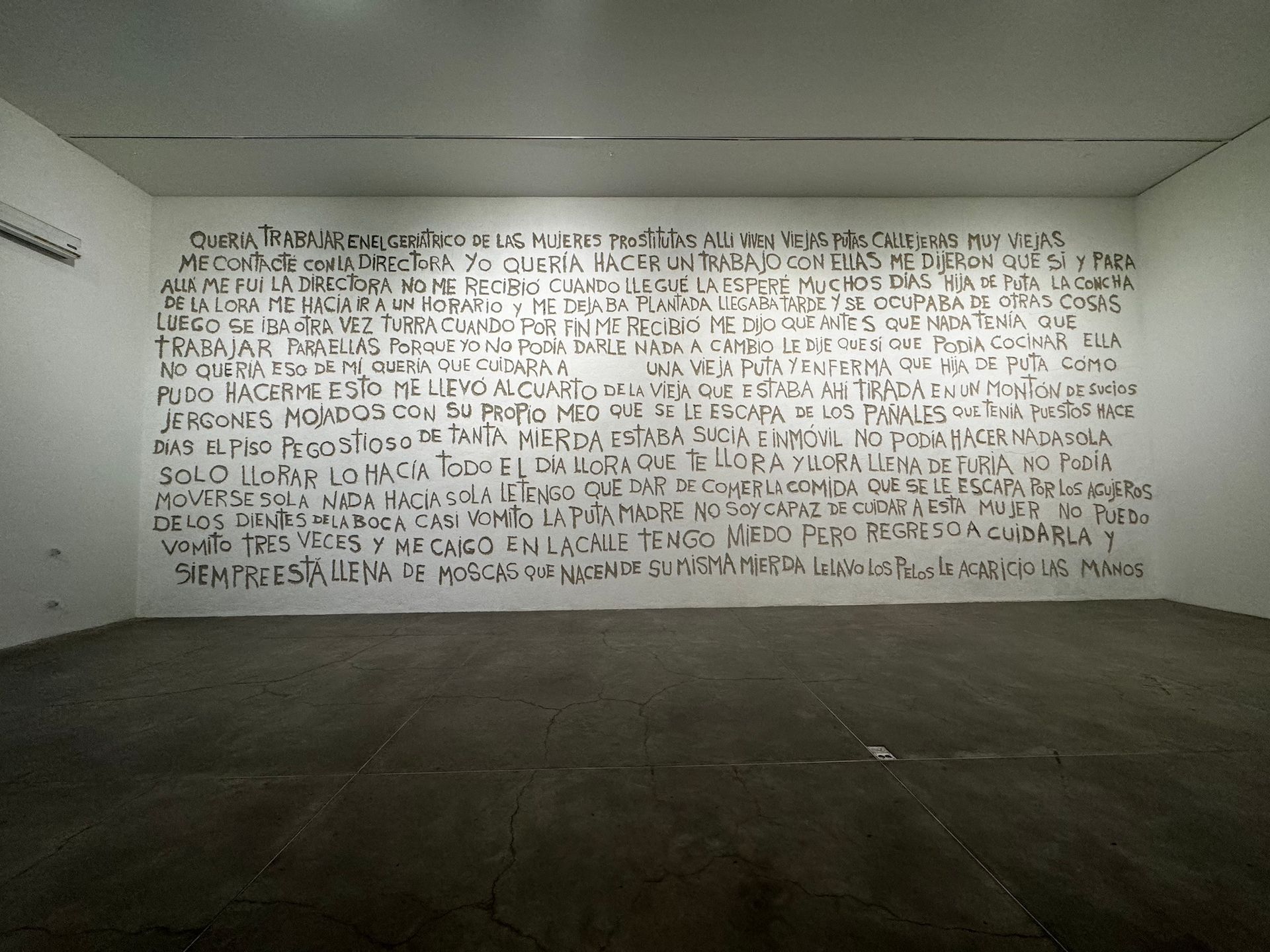

Ana Gallardo’s Extract of a failed project (2011-24) at the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo before it was removed Photo by Edgar Alejandro Hernandez

Such admonishments are the new norm. The Morena party trounced the opposition at the ballot box in June, and Sheinbaum’s new “woman’s hour” administration has wasted no time in continuing with the daily propaganda and divisive discourse. Curators working in Mexico must adapt and museum leadership should be prepared to face public disapproval online and in their galleries, but the Muac and Museo Tamayo’s handling of that criticism cannot become the standard response. Museums that wilfully censor artists with whom they have entered yearslong partnerships forswear their missions to promote social exchange and learning through art.

If a museum cannot stand firm in defiance of demagoguery and nativism, it is a sign that its leaders and curatorial officers are no longer fit to act as mediators between artists and their public. Such fitness must now be measured through an understanding of the local audience’s extraordinary sensitivity to topics like social inequality, class, identity and belonging, which curators working from abroad will struggle to address if they do not enjoy working relationships with local groups devoted to such causes. Mexico City’s museums will have to recalibrate their practices and tip the scales heavily towards community engagement if they want to continue furthering their urgent mission to foster understanding and exchange in a country that is becoming increasingly insular. We look forward to a new museum practice in which acts of censorship—like those perpetrated towards Beier and Gallardo—become, once more, aberrant.

María del Carmen Barrios Giordano is a critic, curator and researcher from MexicoEdgar Alejandro Hernández is a critic, curator, journalist and researcher from Mexico