In the months after Van Gogh mutilated his ear, he created just two paintings of the hospital in Arles in which he stayed. By a stroke of good fortune, both were bought in the 1920s by the Swiss collector Oskar Reinhart, though from different dealers. On Reinhart’s death they became part of his museum, which has until recently been prohibited from lending.

This restriction has now been modified, and the first group of loans are coming to London’s Courtauld Gallery for the exhibition Goya to Impressionism: Masterpieces from the Oskar Reinhart Collection (14 February-26 May). The museum in Reinhart’s atmospheric villa in Winterthur, just outside Zurich, is temporarily closed for building work and is due to reopen in January 2026. In the meantime, the paintings were available for the Courtauld show.

The pair of Van Goghs, The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles and The Ward in the Hospital at Arles, will be among the show’s highlights. Both were begun in the second half of April 1889, at a time when the artist was sleeping in the hospital, but allowed to paint during the day.

This was four months after Van Gogh had mutilated his ear, which had precipitated the abrupt departure of his colleague and lodger Paul Gauguin. His physical wound had healed well, but he was mentally scarred by the trauma.

Hospital garden

The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles (April-May 1889) depicts part of the arcaded cloister-like courtyard with its colourful enclosed garden. The male patients were housed on the upper level, on the right in the painting, and Van Gogh must have loved to escape from the noisy and crowded ward to enjoy the springtime flowers.

I always imagine that the man with a hat seated by the edge of the covered terrace (and apart from the other patients) is Van Gogh himself, perhaps planning this very picture. When he actually painted it, he went to the other side of the courtyard, the south-east corner, so he could include the male terrace and ward. The female patients were in the wing to the left in the picture.

Detail of Van Gogh’s The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles (April-May 1889)

Oskar Reinhart Collection “Am Römerholz”, Winterthur

Vincent gave a detailed description of the painting in a letter to his sister, Wil: “It’s an arcaded gallery like in Arab buildings, whitewashed. In front of these galleries an ancient garden with a pond in the middle and 8 beds of flowers, forget-me-nots, Christmas roses, anemones, buttercups, wallflowers, daisies etc. And beneath the gallery, orange trees and oleanders. So it’s a painting chock-full of flowers and springtime greenery. However, three black, sad tree trunks cross it like snakes, and in the foreground four large sad, dark box bushes.”

Recent photograph of the courtyard garden, reconstructed to look like Van Gogh’s paintingDerek Harris / Alamy Stock Photo

The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles is such a carefully composed and exuberant painting that it is difficult to believe it was made by someone who was suffering as he was. Its composition, with three cropped trees, was inspired by the Japanese prints which Van Gogh so admired. The tree trunks break up the geometry of the flower beds and the two wings of the building. The goldfish in the central pool add a delightful touch.

Van Gogh also made a drawing of a similar scene, using a thick reed pen. At first glance it may appear to be the same view as the painting, but the drawing shows the courtyard from a different angle, making the trees appear less dominant. Drawn in the first few days of May 1889, it was a farewell work. The artist left on 8 May to voluntarily move to what was then regarded as an asylum just outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

Van Gogh’s drawing Garden of the Hospital (May 1889)

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

We can reveal that the painting of the courtyard garden almost became the first Van Gogh to be acquired by London’s National Gallery, even before the Sunflowers August 1888) and Van Gogh’s Chair (December 1888) were bought in the winter of 1923-24.

However, in 1922 The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles was offered to what was then known as the National Gallery Millbank (now Tate) for 2,500 guineas (£2,625). This potential acquisition was considered by the gallery’s trustees in November.

In January 1923 the trustees were informed that the Van Gogh had been “sold at a higher price”. The private collector who outmanoeuvred the London gallery was Reinhart, who acquired it via the Paris-based art trade agent Alfred Gold in December 1922. The Reinhart archive suggests that he paid 150,000 francs (£6,000), more than twice what had been considered by the National Gallery.

It was to be more than a century later that The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles was lent abroad, to London’s National Gallery. It went to the exhibition Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers, which closed on 19 January. When the London curators negotiated the loan, they had no idea that they had almost bought the picture in 1922.

But if the purchase had gone ahead, then a year later the National Gallery trustees might well have had second thoughts about acquiring the Sunflowers. This turned out to be a bargain: Sunflowers was bought in March 1924 for £1,304, half the price which had been mooted for the courtyard garden picture. By this time Samuel Courtauld had provided a substantial fund to buy Impressionist and Post-Impressionist work for the gallery.

The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles was already in London for the National Gallery’s temporary show Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers. It will now be going into the Courtauld exhibition on 14 February. There it will be joined by Reinhart’s other Van Gogh, The Ward in the Hospital at Arles.

The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles was already in London for the National Gallery’s temporary show Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers. It will now be going into the Courtauld exhibition on 14 February. There it will be joined by Reinhart’s other Van Gogh, The Ward in the Hospital at Arles.

Hospital Ward

Van Gogh’s The Ward in the Hospital at Arles (April-October 1889)

Oskar Reinhart Collection “Am Römerholz”, Winterthur

Although Van Gogh described the two paintings as “pendants” (a pair), they could hardly be more different in tone and atmosphere. The Ward in the Hospital at Arles shows the men’s ward, where Van Gogh would have slept (or tried to sleep, in what must have been a noisy and uncomfortable environment). The claustrophobic 30-metre long ward is dominated by the double row of curtained beds. At the far end is a prominent crucifix, marking the entrance to the chapel.

Vincent also described this picture in the same letter to his sister: “A very long ward with the rows of beds with white curtains where a few figures of patients are moving. The walls, the ceiling with the large beams, everything is white in a lilac white or green white. Here and there a window with a pink or bright green curtain. The floor tiled with red bricks. At the far end a door surmounted by a crucifix.”

Although the composition was largely finished while Van Gogh was at the hospital, six months later he added the stove in the foreground and what he described as “a few grey or black shapes of patients” huddled around it. Vincent admitted to his sister that “it’s annoying to paint figures without models”—and these additions from his memory are not entirely successful.

Dr Félix Rey, who had treated Van Gogh after the ear incident, claimed 40 years later that the group of patients in the picture included “a self-portrait of the painter”. If so, he is presumably the man with a straw hat who is reading a newspaper.

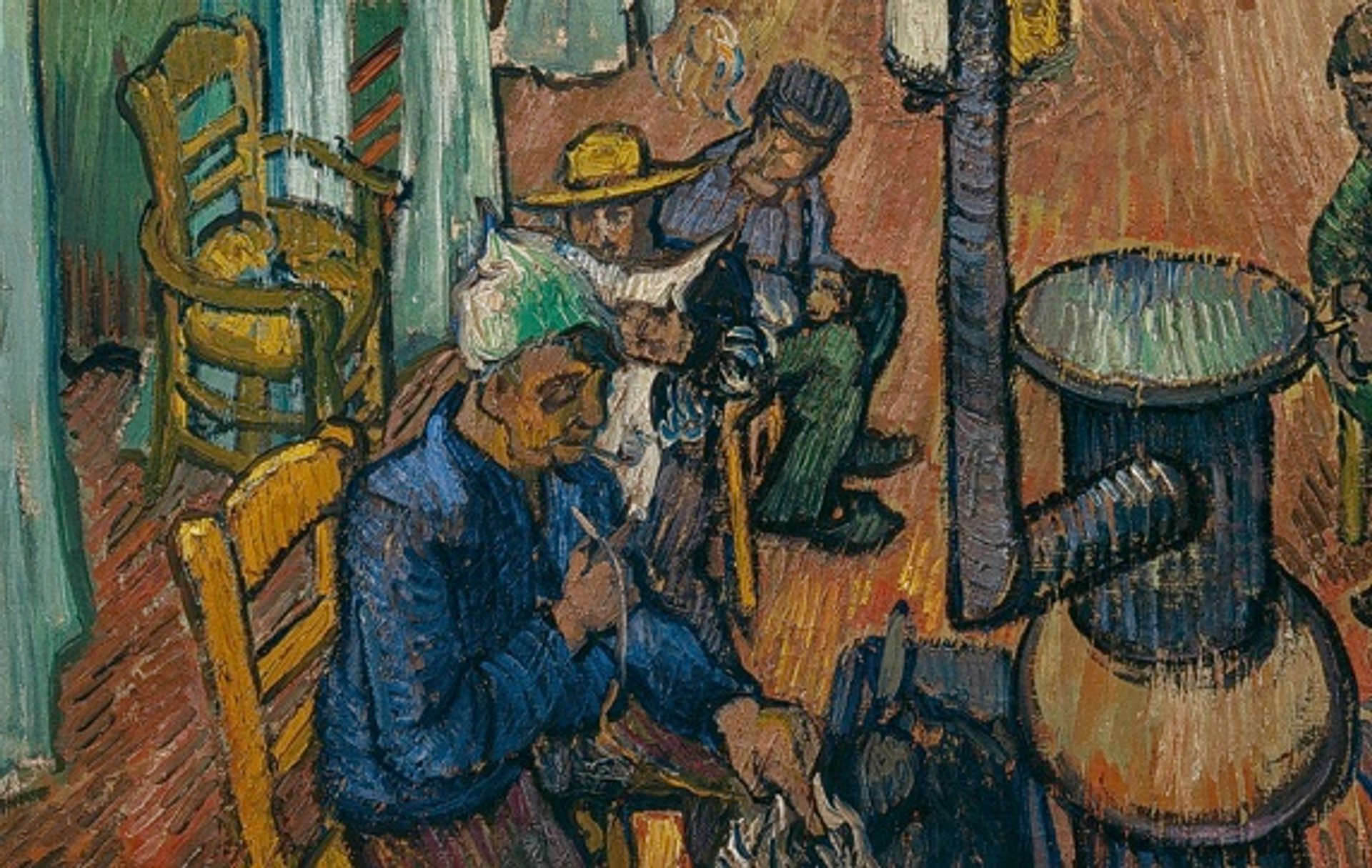

Detail of Van Gogh’s The Ward in the Hospital at Arles (April-October 1889)

Oskar Reinhart Collection “Am Römerholz”, Winterthur

The Ward in the Hospital at Arles was bought in 1925 for 250,000 francs (then £10,000), after having been owned by Elizabeth Workman, the British wife of a wealthy shipbroker. The sale shows how quickly prices for Van Goghs were rising in the 1920s. At the time it seems that Reinhart did not realise that he had fortuitously acquired the only two Van Gogh paintings depicting the Arles hospital.

Hospital to arts centre

The Arles hospital had been converted from a 1573 orphanage and it continued in operation in its ancient building until 1986, when a modern facility was established on the southern outskirts of the city. Most of the original hospital was then converted into a cultural centre, with a large library established in the shell of the wing where the men’s ward had been located.

The space once occupied by the chapel was taken over and converted for the municipal archives. It is there that the few 1888-89 municipal documents concerning Van Gogh’s stay are now housed, including a petition signed by dozens of his neighbours arguing that he was dangerous and should be dispatched to an asylum.

Some years ago, I requested to see the original petition in the archive. It was an eerie experience to read the document just metres away from where Van Gogh’s bed would have stood.

Other Van Gogh news:

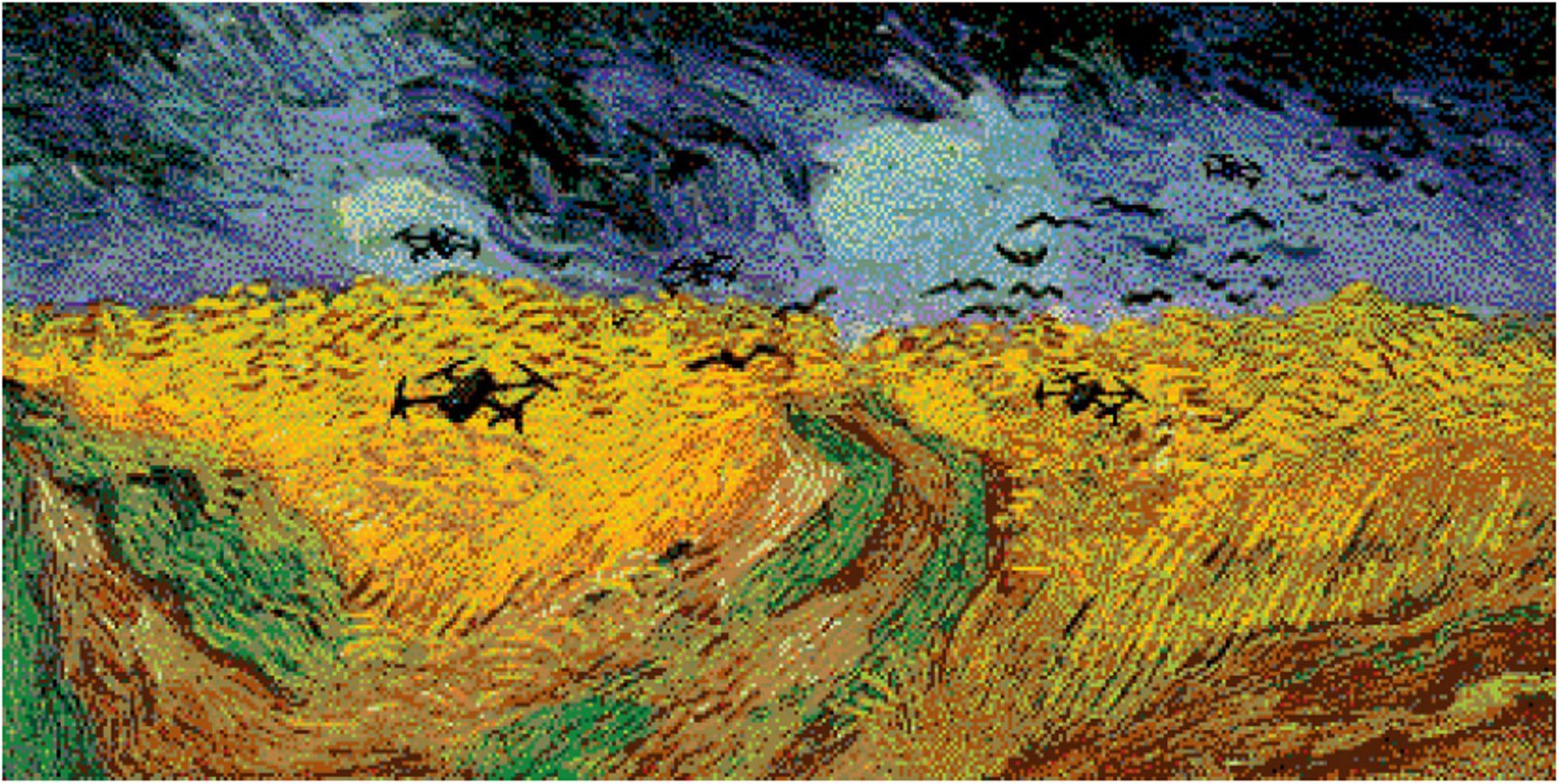

The National Gallery’s Van Gogh: Poets & Lovers (14 September 2024-19 January 2025) closed after receiving 335,000 visits. This was a record for its ticketed exhibitions, just beating Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan (2011-12). The National Gallery’s Van Gogh figure compares with 422,000 for Tate Britain’s Van Gogh and Britain (2019) and 411,000 for the Royal Academy of Arts’ The Real Van Gogh: The Artist and his Letters (2010).Ai Weiwei at London’s Lisson Gallery (7 February–15 March) includes a work inspired by Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows (July 1890). Constructed with toy bricks and over three metres wide, the Chinese artist has replaced the crows with surveillance drones.

Ai Weiwei’s Wheatfield with Crows (2024)

Lisson Gallery, London